What Comes Next for Thacker Pass?

Formidable Asset Management (“Formidable”) has closely followed Lithium Americas Corp (NYSE: LAC) as part of our research in green energy; click here for our January 2021 piece on the approval of the company’s Thacker Pass project.

What is Thacker Pass? The Thacker Pass Project (the “Project”) is attractive due to its estimated production capacity, reasonable operating costs, and strategic location in the U.S.[1] The Project, forecast to begin major construction in 2022, would become one of the first—and largest—lithium mines in the U.S. over its active mining life.

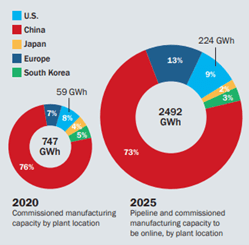

Why is it important? Beyond the obvious impact on LAC’s potential revenue, lithium is positioned at the beginning of a battery supply chain consisting of raw materials mining, refinement, electrochemical production, cell manufacturing, and battery assembly—a supply chain dominated by China and in which the United States does not meaningfully participate. The Biden administration recognizes the need for domestic lithium as a matter of both environmental and national security. A National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries (2021-2030) provides guidance on developing local capabilities, including securing a “reliable supply of raw, refined, and processed material inputs for lithium batteries.” Increasing adoption of electric vehicles will generate fewer emissions than conventional vehicles, while establishing a resilient, domestic supply chain will reduce dependence on external suppliers. The Thacker Pass Project is a milestone in U.S. clean energy efforts and will set a precedent for future domestic initiatives.

Figure 1. Global cell manufacturing capabilities. Source

What happened after the Project’s approval? On January 15, 2021, the Project received approval from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Shortly thereafter, lawsuits were filed—one by a nearby rancher[2] (February 11, 2021) and another from four collaborating non-governmental organizations[3] (February 26, 2021), each seeking to overturn the approval. Notable allegations from the complaints include failure to adequately address and mitigate potential Project harm to wildlife, environment (water and air), and communities living within or near the Project site. On July 29, 2021, the Court permitted two Native American groups[4] to join the lawsuit as plaintiffs. On August 2, 2021, a third tribal group requested involvement and awaits approval. The groups are primarily concerned with potential damage to religious and historical sites resulting from pre-mining activities and are seeking a preliminary injunction (discussed later)[5]. The Court will rule on the groups’ pre-mining concerns by the end of August 2021. The tribes’ further charges are comparable to prior plaintiffs’ allegations and will be addressed in the final Court ruling. The judge believes these additions will not affect the overall case timeline.

As it stands, there are seven total plaintiffs[6] (one pending) contesting BLM’s Project approval. We are most concerned with allegations presented by the four collaborating non-governmental organizations (NGOs), but any of the plaintiffs’ complaints could result in a hindrance to the Project’s mining activities.

On May 27, 2021, the four NGOs filed a motion for preliminary injunction to halt excavations on historical sites until after the Court’s forecast January 2022 merits ruling. The Court ruled against the motion on July 23, 2021, deeming the excavations would not cause plaintiffs significant, irreparable harm.

This decision will not affect the overall Court ruling. As part of the preliminary injunction process, parties must submit arguments for/against the initial allegations (in this case, nine total). While these claims did not affect the injunctive ruling, they provide vital insight into the controversies and rationalizations that will be addressed in the overall Court ruling. In other words, this is necessary information that may impact the outcome of the lawsuit in determining if, when and how the active mining may take place.

What is next?

The Nevada District Court estimates a ruling on BLM’s approval by December 2021 and a summary judgment, or final decision, in January 2022.

Prior to major construction and a final Court ruling in 2022, Lithium Nevada Corporation (LNC, a wholly owned subsidiary of LAC), must conduct the following pre-mining operations:

- Obtain permits for, and perform, excavations and data collection on 21 historic sites.

- Receive permits for mine reclamation, water pollution control, and air quality (estimated Q4 2021).

- Provide a financial guarantee for mine reclamation and complete a subsequent bonding process.

What is at stake?

Others have written about the environmental conundrum raised by this lawsuit, noting the juxtaposition of first order effects (i.e., potential disruption of sage grouse habitats as well as cultural considerations (and other similar cases) and longer-term outcomes (a transition from fossil fuels permitted by materials like lithium).

While that is beyond the scope of this whitepaper, it is worth noting the continued insistence in the media that the Project’s approval was railroaded in the last days of the Trump administration when, in fact, the BLM staff associated with the process are long-tenured, non-political appointees is disingenuous. Initial work on the Project began during the Obama administration (2011), and although the Trump administration put in place measures to streamline BLM reviews, they were not specific to the Project.

If the United States is at all serious about achieving even a modicum of its green energy objectives, projects like Thacker Pass need to be supported against the efforts of groups vehemently opposed, not specifically to this project or those like it, but seemingly to all extraction. The stance in this case seemingly compelled Glenn Miller, a founder of Great Basin Watch (one of the plaintiffs) to resign from its board of directors. As he stated in a piece he wrote for The Sierra Nevada Ally, “this mine is indeed relatively benign but will be a major source of lithium, which is critical for mitigating the transportation contribution to carbon buildup in the atmosphere and the resulting climate change. Overall, I feel that this mine is environmentally beneficial, due to the importance of the metal, and the projected lack of long-term problems that are common in other mines.”

How can I learn more?

In the following, we provide an overview of how the approval process works, as well as the history of Thacker Pass in particular. We then look at the plaintiffs’ original complaints and the judge presiding. Finally, we review the initial preliminary injunction request, judge’s decision, and arguments from both sides, including each party’s stance on the ongoing allegations that are relevant to the final Court decision.

Introduction

In 1976, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) established land use planning requirements for every on-the-ground action the United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management (BLM) undertakes. Land use plans are essential for guiding BLM activities to reach the goals outlined in the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Strategic Plan. Categories of plans include resource management plans (RMPs) and management framework plans (MFPs). BLM develops RMPs in collaboration with communities to provide guidance on (1) resource allocation and multiple use of public lands, (2) management strategies to protect resources, and (3) establishing systems to monitor and evaluate resources and their respective management protocols over time[7]. The FLPMA ensures BLM’s coordination with state, local, and tribal governments to help solve discrepancies between BLM’s land-use plans and local land-use plans, to the maximum extent consistent with federal law and the purposes of FLPMA[8]. According to the Land Use Planning Handbook H-1601-1[9], public lands must be managed in a manner that protects the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource, and archaeological values, that, where appropriate:

- Preserves and protects certain public lands in their natural condition

- Provides food and habitat for fish, wildlife, and domestic animals

- Provides for outdoor recreation and human occupancy use

- Recognizes the Nation’s need for domestic sources of minerals, food, timber, and fiber from public lands

Most actions the BLM takes to implement its land-use plans are reviewed under the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), either through formulation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or other Environmental Assessments (EAs) or related documents. An EIS is a comprehensive document that analyzes the impacts of a federal action that significantly affects the human environment. The document outlines the need for such an effort and discusses its direct environmental effects, proposing mitigation solutions where appropriate. The EIS is accompanied by a Record of Decision (ROD), which affirms the BLM’s decision to either approve or deny the proposed action[10]. Click here to see a graphic representation and here for a detailed overview of BLM’s land-use planning, clearance, and approval process. Amendments and revisions are enacted to allow for activity that does not apply to current land-use plans. Click here for a graphic representation of the steps involved in submitting a land-use amendment.

Collaboration and public participation are highly encouraged throughout the planning process. BLM provides the following opportunities, or scoping periods, that allow the public to comment on, protest, and potentially influence land-use decisions[11]:

- Comment on initial planning criteria – 30 days

- Comment on Draft RMP / Draft EIS – minimum 90 days

- Protest period (resolve protests prior to ROD) – minimum 30 days

Thacker Pass Project

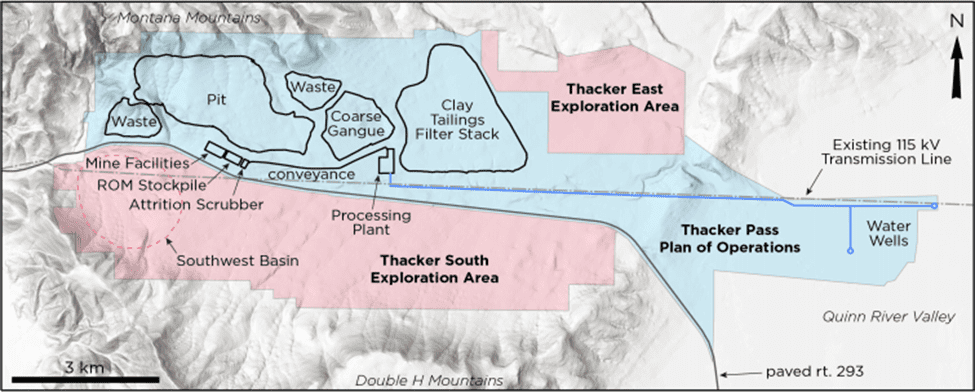

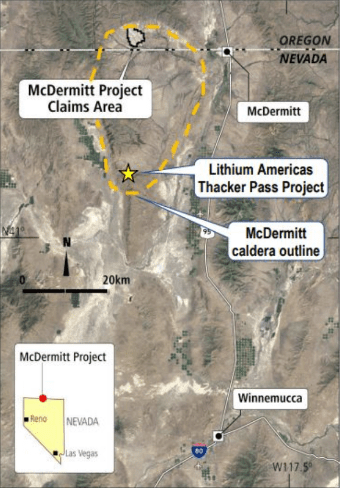

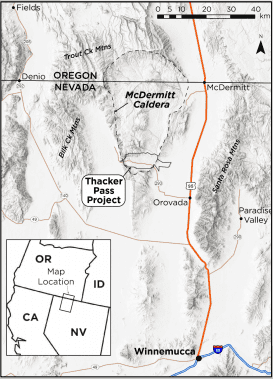

Figure 2. Thacker Pass Project Layout. Source: Lithium Americas July 2021 Corporate Presentation

In September 2019, Lithium Nevada Corporation (LNC), a wholly owned subsidiary of Lithium Americas Corp. (NYSE: LAC) initiated its mining efforts by submitting two Plans of Operations for locatable minerals projects to the Winnemucca District Office of the BLM. The filings included plans for the proposed Thacker Pass mine, the necessary processing and ancillary support facilities, a plan for reclamation (closure) of the mine and its facilities, and a plan for exploring north and south of the mine and its facilities throughout the mine lifetime. These plans constitute the Thacker Pass Project (the “Project”), which will operate entirely on public lands administered by the BLM in Humboldt County, Nevada, approximately seventeen miles west-northwest of Orvada. In response to LNC’s Plan of Operations, BLM prepared the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine Project EIS to analyze the proposed action (Alternative A) and three alternatives (Alternative B, C, D) and ultimately determine the Project’s utility, environmental footprint, and overall feasibility. Alternatives A – D considered options to refill, also known as backfill, all excavations performed in the Project. BLM released the Final EIS (FEIS) to the public on December 4, 2020 and conducted a 30 day commentary/review period. On January 15, 2021, Winnemucca District Manager, Ester M. McCullough, officially approved Alternative A for the Project by submitting an ROD[12].

Under Alternative A, LNC will construct an open pit lithium mine and processing facility in the Thacker Pass basin. Project development will occur in two phases, each containing a construction and an operational phase, over the 41-year mining life. Phase 1 begins with initial construction that will occur over four years and generate an open pit mine, lithium processing plant, and sulfuric acid manufacturing plant with an estimated annual production capacity of up to 33,000 tons of battery-grade lithium carbonate (Li2CO3). Phase 1 operations following initial construction will begin in year three. Phase 2 occurs from years 5 – 41 and includes additional construction that will double production capacity to 66,000 tons of Li2CO3 by year six. LNC will initiate Phase 2 operations in year seven to achieve this heightened capacity and sustain it through Project completion. LNC will spend a total of $873.5 million over the initial four-year construction period to account for high short-term labor demand associated with construction projects. Regarding operational costs, LNC will spend $153 million for phase 1 operations (33kta Li2CO3) and $262 million over the course of its second operational stage (66kta Li2CO3). The total Project area covers 17,933 acres of land, including 10,468 acres and 7,465 acres for mining and exploration, respectively. The Project’s total disturbance footprint will consist of approximately 5,695 acres, and LNC will perform ongoing mitigation and reclamation efforts throughout the Project duration. Once the mine life has ended, LNC will completely backfill the open pit, and the Project will enter a reclamation and closure period for a minimum of five years[13].

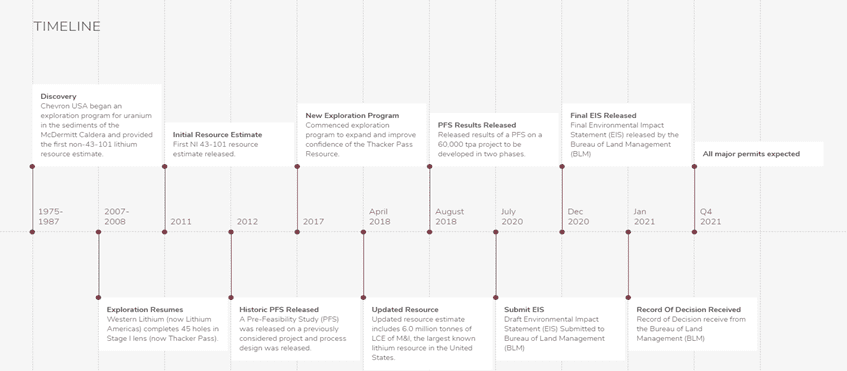

Figure 3. Thacker Pass Project Timeline. Source: Lithium Americas Website

The origins of the Thacker Pass Project date back to 1975, when Chevron USA started an exploration program in the McDermitt Caldera (volcanic crater) located in southeastern Oregon and northern Nevada. From 2007-2008, Western Lithium (now LAC) expanded upon these nascent exploration efforts and ultimately released an initial resource estimate covering the Thacker Pass lithium deposit in 2011. LAC published a Pre-Feasibility Study (PFS) in 2012 to determine a possible mining project and process design over the target area. In 2017, LAC conducted a further exploration program over the Thacker Pass Resource to expand its confidence in the area. The company constructed an additional resource estimate in April 2018 that deemed the Thacker Pass Resource the largest known source of lithium in the United States. Finally, LAC released results of an updated PFS of the Thacker Pass Project in August 2018 before seeking approval for its Plans of Operations from the BLM.

Project Approval Timeline

September 2019 – LNC submits initial Plans of Operations to Winnemucca District Office of the BLM

January 21, 2020 – BLM publishes Notice of Intent (NOI) to prepare EIS

- Public scoping period – January 21 – February 27 (extended 7 days)

February 5 – 6, 2020 – Public scoping meetings for the EIS held in Winnemucca and Orovada, Nevada, respectively

July 31, 2020 – BLM publishes Notice of Availability (NOA) for the Draft EIS (DEIS)

- Public scoping period – July 31 – September 14, 2020

August 19 – 20, 2020 – Public information meetings held virtually

December 4, 2020 – BLM publishes NOA for the Final EIS (FEIS)

- Public scoping period – December 4, 2020 – January 4, 2021

January 15, 2020 – BLM publishes ROD and officially approves Alternative A for Thacker Pass Mining Project

Thacker Pass Lawsuit

Overview

Court: United States District Court – District of Nevada

Case No.: 3:21-cv-00103-MMD-CLB

Plaintiffs: Western Watersheds Project; Great Basin Resource Watch; Basin and Range Watch; Wildlands Defense; Reno-Sparks Indian Colony; Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu/People of Red Mountain (Pending: Burns Paiute Tribe)

Defendants: United States Department of the Interior; US Bureau of Land Management; Ester M. McCullough, District Manager, BLM’s Winnemucca Office

Defendant-Intervenor: Lithium Nevada Corp.

Case No.: 3:21-cv-00080-MMD-CLB

Plaintiffs: Bartell Ranch, LLC / Edward Bartell (co-owner of Bartell Ranch, LLC)

Defendants: Ester M. McCullough, District Manager, BLM’s Winnemucca Office; Bureau of Land Management

Timeline

February 11, 2021 – Bartell Ranch, LLC, and Edward Bartell challenge[14] Ester M. McCullough’s (i.e., BLM) approval of the Thacker Pass Project under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and seek injunctive relief to enjoin all Project activities until the Court rules on the merits of BLM’s decision.

February 26, 2021 – Four collaborating non-governmental organizations (NGOs) challenge[15] BLM’s decision to grant Project approval under the APA and request injunctive relief until the final merits ruling.

March 2, 2021 – Nevada District Court reassigns[16] both cases to one District Judge to promote judicial efficiency and to avoid duplicative filings by the parties. Reassignment will not result in prejudice to the parties. All future pleadings will bear case number 3:21-cv-00103-MMD-CLB.

May 12, 2021 – The Court grants LNC’s Motion to Intervene as a defendant.

May 13, 2021 – LNC notifies Plaintiffs it intends to begin ground disturbance on June 23, 2021, consisting of initial excavations and digging associated with the unreleased “Historical Properties Treatment Plan.”

May 27, 2021 – Plaintiffs file a Motion for Preliminary Injunction to prevent any ground disturbance associated with the project from occurring until the Court rules on the merits of BLM’s approval.

- Parties agree to no ground disturbance activities of any kind before July 29, 2021.

June 24, 2021 – BLM and LNC file separate response briefs[17],[18] to Plaintiffs’ motion for Preliminary Injunction.

July 1, 2021 – Plaintiffs file a reply brief[19] in response to BLM and LNC.

July 20, 2021 – The Court permits two Native American tribes, Reno-Sparks Indian Colony and Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu/People of Red Mountain, to join as plaintiffs primarily concerned with damage to religious and historical sites.

July 23, 2021 – The Court rules against the motion for Preliminary Injunction.

August 2, 2021 – The Burns Paiute Tribe files a motion[20] to intervene as a third Native American plaintiff.

- August 5, 2021 – LNC and BLM do not oppose the motion to intervene.

August 12, 2021 – Deadline for defendants to submit response(s) to Native American groups’ allegations

December 2021 – Projected date of Court ruling on ROD.

January 2022 – Projected date of summary judgment (judge’s final ruling on the case)

Pre-Mining Operations

LNC aims to begin major ground-disturbing activities by early 2022 (after the summary judgment) and will provide a 60-day notice prior to commencement. Before conducting major ground-disturbing activities, LNC must complete the following:

- Perform various cultural mitigation procedures, including excavation and data collection, outlined in the Historical Properties Treatment Plan (HPTP).

- BLM must first issue an Archeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) permit to LNC and field work authorization permits to Far Western Anthropologic Research Group (LNC’s cultural contractor).

- Obtain permits for (1) mine reclamation, (2) water pollution control, and (3) air quality from the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection (NDEP).

- Provide a financial guarantee to BLM and NDEP for the Project and complete the subsequent bonding process.

Lithium Americas expects to receive all major permits by Q4 2021.

All Complaints

In this paper, we focus primarily on allegations presented by four collaborating NGOs. There are seven[21] total plaintiffs (one pending) involved in the Thacker Pass litigation. Any of the plaintiffs’ complaints could result in a delay or discontinuance of Project activities.

Bartell Ranch, LLC / Edward Bartell

Bartell Ranch possesses a federal grazing permit, private ranch lands, and water rights, which may be threatened by mining operations. Project mining may also irreparably harm fish, wildlife, wetlands, and streamflows, including Lahontan cutthroat trout habitat. This species is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Plaintiffs in this case believe BLM’s ROD violates NEPA and FLPMA guidelines (same as NGO allegations).

Reno-Sparks Indian Colony & Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu/People of Red Mountain (Pending: Burns Paiute Tribe)

The Native American groups recognize Thacker Pass as a sacred, “massacre site” where their ancestors were brutally killed in the 1800s. Their primary complaint is that BLM failed to consult them regarding LNC’s Historic Properties Treatment Plan (HPTP), which is required by the National Historic Prevention Act (NHPA) to mitigate damage to historic and cultural lands within the Project area. The groups are seeking a preliminary injunction to delay these pre-mining operations. Other concerns include Project damage to water, air, and wildlife, namely the golden eagle, deemed a culturally sacred animal by the group’s religion.

BLM has been in contact with four tribal governments since October 2018 to address tribal concerns and inform them on Project advancements. The agency began formal consultations in December 2019 by sending certified letters to the tribes. Additionally, the agency shared email updates and copies of BLM materials throughout the Project review. During this time, the selected tribes did not present any comments or concerns involving mining operations.

The People of Red Mountain group describes itself as a descendant of the Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone tribe—one of four tribes who participated in consultations and did not protest the Project. They believe building a mine over the massacre site is equivalent to “building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery.”[22] LNC objects to this group’s claims as it is not a federally recognized tribe under the NHPA.

The Reno-Sparks tribe did not take part in Project consultations with BLM. While BLM’s justification for excluding the tribe is unknown, one might point to the tribe’s location as a potential factor. The group is located 229 miles away from Thacker Pass—further than any of the tribes involved in consultations. The group’s tribal historic preservation officer, Michon Eben, states, “Just because regional tribes have been isolated and forced onto reservations relatively far away from Thacker Pass does not mean these regional tribes do not possess cultural connections to the pass.”

The Burns Paiute Indian Reservation is located nearly 200 miles away from Thacker Pass, but it claims to inhabit territory that extends into the Project area. The tribe did not learn about the proposed Project until May 2021.

This development raises the following questions. How many Native American tribes should have been consulted during Project review? What selection criteria (e.g., location) did the agency use to determine participants? The presiding Judge has granted defendants until August 12, 2021, to respond to the tribes’ complaints. She will rule on the subject later in the month. If LNC intends to begin HPTP excavations prior to August 23, 2021, it must notify the judge as an emergency order (ruling) may be required to resolve the tribes’ allegations prior to HPTP activities. LNC still needs to obtain necessary permits before it can perform this action[23].

NGOs

The collaborating NGOs (hereon designated “plaintiffs”) filed their initial complaint on February 26, 2021, under the APA. They alleged BLM’s approval of the Project’s mining operations and exploration plans to be in violation of FLPMA, NEPA, and unspecified other federal laws and their respective implementation regulations. As previously stated, BLM’s review and consideration (ROD) of mining plans and operations on public lands are subject to FLPMA guidelines. For any plan amendments, BLM must act in accordance with NEPA requirements. Since BLM determined the Project would constitute a major federal action, the agency amended the plan by developing an EIS, which is subject to review under NEPA5. In summary, plaintiffs seek review of BLM’s ROD, FEIS (i.e., NEPA), and related Project approvals.

Plaintiffs allege the following offenses:

- Violation of the wildlife portions of the controlling RMPs

- Violation of the visual resource portions of the RMPs

- Project approval relied upon unsupported assumptions that LNC held “valid existing rights” under the Mining Law of 1872

- Failure to adequately analyze potential mitigation measures and their effectiveness

- Failure to adequately analyze direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts of the Project

- Failure to adequately analyze the background/baseline conditions of the Project

- Failure to ensure compliance with air and water quality standards and protect public resources

- Failure to determine reclamation costs and obtain related financial assurances

- Authorization of unnecessary or undue degradation of the land within the Project area

Judge Miranda Du

Overseeing proceedings is Miranda Du, who graduated with honors from UC-Davis with undergraduate degrees in Economics and History and obtained her J.D. from UC-Berkeley. In 1994, she joined McDonald Carano Wilson LLP & served as Chair of the Employment & Labor Group until her appointment to the bench. She was appointed by President Obama and took her oath on April 23, 2012, rising to chief judge on September 2, 2019.

Judge Du has ruled on sage grouse matters in the past, albeit under different scenarios than seen here. She ruled against off-road enthusiasts deemed to be disturbing sage grouse in a case with far fewer economic consequences. She also issued a mixed ruling vis-à-vis plans for implementation of Federal sage grouse protections that was fought by Nevada counties and miners. Interpretation of the ruling concludes that though she agreed with the counties and miners, in part, the ruling only delayed implementation of onerous sage grouse protections, subject to amended filing of an amended EIS by the BLM. In other words, it is sage grouse two, people zero.

Preliminary Injunction Request

Plaintiffs filed a motion for preliminary injunction on May 27, 2021. A preliminary injunction preserves the status quo of trial-related activities until the Court can rule on the merits of the lawsuit, which can take several months or more to complete. In this case, the Court expects to reach a final decision in early 2022—prior to scheduled major construction. In the interim, LNC must obtain necessary permits, financial guarantees, and perform a series of excavations—manual and mechanical (presumably via backhoe)—to collect historical/cultural data to fulfillment HPTP requirements in accordance with the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). The NHPA required HPTP protocols after BLM determined the Project would adversely impact lands eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Plaintiffs seek to enjoin activities under HPTP and any other mining that may occur prior to the merits ruling.

A plaintiff seeking preliminary injunction must show each of the following[24]:

- It is likely to suffer irreparable harm if injunction is not granted.

- It is likely to succeed on the merits.

- The balance of equities tips in its favor.

- An injunction is in the public’s interest.

A deficiency in any one of the required elements precludes extraordinary relief[25]

Preliminary Injunction Battle

As stated above, plaintiffs must fulfill all four requirements—irreparable harm, likelihood of success on merits, balance of equities, and public interest in favor of relief—to be considered for a preliminary injunction. While injunctive relief is applicable to activities in the immediate-term, one of the criteria—likelihood of success on the merits—requires participants to demonstrate a probability of success or failure with respect to the overall lawsuit. In other words, parties must consider long-term consequences when advocating for/against injunctive relief. As a result, the plaintiffs and defendants in this case address all nine allegations from the original complaint in their responses to the motion for preliminary injunction. It is important to recognize these nine arguments, listed under section II: Plaintiffs show a likelihood of success on the merits of their claims, are ongoing and may influence the overall outcome of the case. In fact, as we’ll see below, the Court denied plaintiffs’ request for preliminary injunction solely due to an inability to demonstrate immediate, irreparable harm from HPTP activity. Thus, the Court has yet to judge the merits of these nine outstanding allegations and their supporting rationale.

Judge’s Decision

The Nevada District Court denied plaintiffs’ request for preliminary injunction on July 23, 2021[26].

“‘An injunction is a matter of equitable discretion’ and is ‘an extraordinary remedy that may only be awarded upon a clear showing that the plaintiff is entitled to such relief.’”[27]

To start, the Court clarified that the only topic relevant to plaintiffs’ preliminary injunction request was activities under the HPTP, which will occur this summer/fall 2021. The Court is targeting early 2022 to reach its final decision on the case, and it believes major Project construction is “very unlikely” to begin before spring 2022 due to winter weather conditions. LNC reaffirmed this estimate as it must complete the HPTP and obtain various permits prior to construction. Thus, the scope of this request was narrow. If LNC decides to conduct additional ground disturbance prior to the merits ruling, or plaintiffs find fault with any other aspect of LNC’s pre-mining operations, plaintiffs may file a renewed motion for preliminary injunction. This is apparent in the Native American groups’ decision to seek injunctive relief from HPTP excavations on grounds of damage to religious and historical sites.

Activities under HPTP will include the following: (1) excavating and collecting data from 21 historic sites; (2) archival research; (3) survey of a Civilian Conservation Corp camp corresponding dump within the Project area; and (4) further digging and investigating of any additional historic lands LNC may harm through its exploratory efforts. Plaintiffs are primarily concerned with excavation of the 21 sites, which will result in 2-25 hand-dug holes at each site and seven mechanical trenches at various locations measuring up to three meters deep and forty meters long. Upon completion, LNC will backfill all disturbed areas to their original compaction.

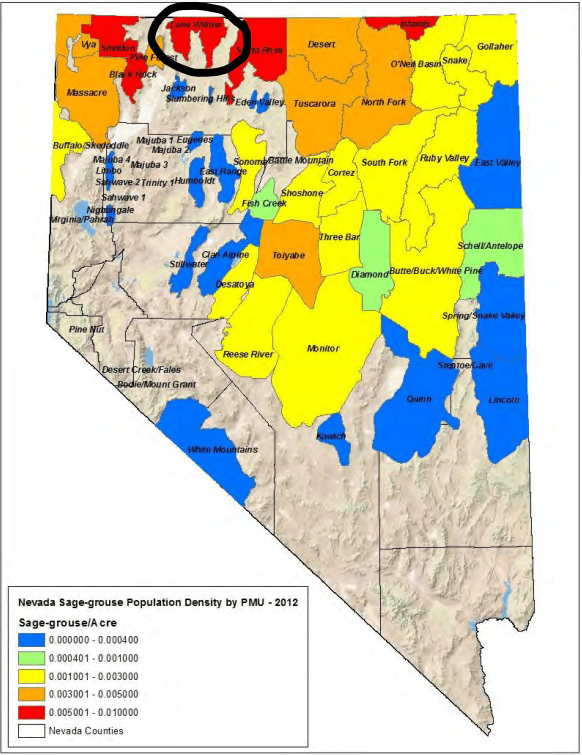

Plaintiffs relied heavily on a declaration given by Dr. Clait E. Braun (declaration not available), a biologist who has studied sage-grouse for over 40 years, to defend their claim. He argued excavations would remove a significant number of sagebrush, which sage-grouse and other wildlife rely on for food and shelter. He added that invasive cheatgrass would replace the sagebrush, which are notoriously difficult to regrow. He noted, “Thacker Pass provides important sage-grouse nesting, brood-rearing, and winter habitats and at least 30 sage-grouse are known to have recently used the Project area.”

The Court determined plaintiffs’ arguments did not meet the “extraordinary” requirements to grant injunctive relief. They deemed Dr. Braun’s points as speculative and nonspecific to actual locations affected by HPTP activity. For example, Dr. Braun claimed he did not know where the holes would be dug, so he could not be certain that any sagebrush would be removed. Furthermore, Dr. Braun’s declaration did not offer any counter evidence to Mark E. Hall’s declaration[28], which suggests any impacts to sage-grouse resulting from HPTP operations will be minimal. Hall questions the suitability of HPTP lands for sage-grouse, which are located near noisy roads (sound pollution) and are positioned at least one or more miles away from any known lek.

All in all, plaintiffs demonstrated de minimus harm that might impact approximately 0.25 acres (0.0014%) of the Project’s 18,000 total acres of Project land (and will at least be partially remediated). The Court concluded, “Under the unique factual circumstances of this case, and given the limited, speculative evidence of imminent harm Plaintiffs presented, they have failed to meet their burden to show they will be irreparably harmed in the absence of a preliminary injunction as the parties await the Court’s merits decision.”

Notes:

- Defendants argued plaintiffs cannot object to activities under HPTP since they are regulated by NHPA as opposed to FLPMA or NEPA—the targets of plaintiffs’ original complaint. A footnote mentions the Court was “generally persuaded” to consider plaintiffs’ plea since the alleged harm would impact sage-grouse—a form of harm plaintiffs’ argued BLM failed to consider in its outstanding complaint. The Court also accepted plaintiffs’ claim that they possessed no other means to object to HPTP activity.

- The Court notes that the parties mentioned additional arguments & cases that were not included in this preliminary injunction decision. Since they were not relevant to HPTP activities, they did not warrant discussion. The Court may consider these allegations in its merits ruling on BLM’s Project approval.

- The Court struck (removed from court record) two declarations plaintiffs presented to support their motion for preliminary injunction:

Preliminary Injunction Arguments

I. Plaintiffs demonstrate imminent threat of irreparable harm

BLM

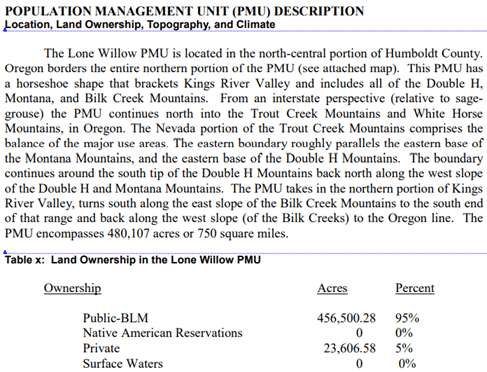

According to BLM, Plaintiffs claim they will face immediate, irreparable harm because of (1) activities under the Historical Properties Treatment Plan (HPTP), and (2) general mining operations throughout the Project life cycle. Regarding HPTP, BLM argues plaintiffs cannot demonstrate irreparable harm because HPTP operations will be minimal and remediated upon completion. For example, per Mark E. Hall’s declaration, HPTP excavations will cover approximately 0.15 acres in the Lone Willow (Sage Grouse) Population Management Unit (PMU) and disturb less than 0.0001% than the entire PMU. In addition, plaintiffs are not able to challenge activities under HPTP because the Court has no basis to enjoin such actions. The plaintiffs’ original complaint specifically refers to BLM’s approval of ROD and FEIS, which are both governed by NEPA and FLPMA. On the other hand, HPTP is controlled by the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), which is independent of NEPA and FLPMA. Regarding actual mining operations, BLM asserts LNC will perform no major ground-disturbing activities in the immediate future. As previously stated, LNC must perform several pre-mining preparations like obtaining necessary permits, carrying out cultural/historical mitigation under HPTP, and ensuring a financial commitment and completion of the bonding process with BLM and NDEP. Thus, plaintiffs’ request for “immediate” relief do not apply to future mining activities.

LNC

LNC restates BLM’s arguments regarding a lack of immediate, irreparable harm. LNC argues the only imminent construction activities are those under HPTP, which it insists are not before the Court (i.e., plaintiffs cannot challenge it). Nevertheless, LNC asserts this mining is both minor, disturbing less than half an acre of land, and can be reclaimed through recontouring and reseeding. In any case, LNC emphasizes that irreparable harm must be “both certain and great”, arguing one or more environmental violations may not be enough to justify the “extraordinary remedy of injunction”. LNC cites a related court case[31] that concluded, “A finding of a NEPA violation alone does not demonstrate irreparable harm.” It adds that the Ninth Circuit has also rejected arguments declaring “any potential environmental injury automatically merits an injunction”[32]. Thus, plaintiffs fall short in their argument.

Plaintiffs

According to plaintiffs, when refuting contentions of “immediate” harm, the defendants exclude major ground-disturbing activities and focus primarily on pre-mining operations scheduled to begin immediately after July 29, 2021. Plaintiffs argue LNC could begin major construction before the Court reaches a final decision on the merits of the case, thus justifying the need for injunctive relief. LNC is “likely” to receive all necessary permits “sometime in July or August of 2021” (per Declaration of geologist Kathleen Rehberg[33]), and the CEO of LNC plans to “commence construction of the Thacker Pass Project in early 2022.” Plaintiffs believe a merits briefing would not conclude until December 2021 or well into 2022 if subsequent motions extend the case schedule. If the initial request for relief does not satisfy the immediacy requirement, plaintiffs might consider filing a second motion for injunctive relief whenever LNC releases its 60-day notice prior to major construction.

Regarding harm from HPTP activities, Plaintiffs assert these actions are included under the ROD and FEIS as mitigation measures, giving the Court the authority to rule on their merits. Plaintiffs claim defendants failed to adequately study the entirety of the plan’s adverse effects. Defendants did not address the irreparable damage excavations would inflict on sagebrush populations, which are notoriously difficult to grow and are depended upon by other wildlife for food and thermal cover, nor did they disclose the magnitude of such digging, which would result in 525 holes up to 4.5ft deep and trenches at seven locations measuring 65-130 feet long and nine feet deep. Invasive cheatgrass is a major threat to sagebrush as well and would replace the plant at excavation sites. This is not “de minimis” disturbance. On a more self-serving note, plaintiffs believe pre-construction will harm their interests in “viewing, utilizing, and experiencing the site in its undisturbed state.”

II. Plaintiffs show a likelihood of success on the merits of their claims

Note: The Nevada District Court has yet to address these allegations (not relevant to immediate activities under HPTP) and may consider any/all arguments in their final merits ruling in 2022.

- Violation of the Wildlife portions of the controlling RMPs

- Violation of the visual resource portions of the RMPs

BLM

According to BLM, plaintiffs argue the agency’s ROD violates certain RMPs. These include the Greater Sage Grouse Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment (ARMPA) and the visual resource management (VRM) requirements of the Winnemucca, Nevada RMP, which were both approved in 2015. BLM argues there is no statute or regulation that requires it to comply with the invoked RMPs, which are neither federal nor state laws. In fact, the RMPs, themselves, do not require BLM to comply with their provisions. The agency also asserts provisions under land-use plans cannot be enforced if they prohibit the exercise of statutory rights under the Mining Law of 1872, which was amended by FLPMA but retains certain protections for mining operations on public lands.

LNC

LNC reiterates the authority of Mining Law over RMP provisions when granting rights to locatable minerals projects. LNC reminds plaintiffs that the following guidelines to not apply to nondiscretionary, locatable mineral projects under the Mining Law: 3% disturbance cap to sage-grouse, appropriate lek buffer distances, seasonal restrictions and noise limitations, and net conservation gain mitigation requirements under ARMPA. Nevertheless, LNC performed multiple mitigation measures including spending millions of dollars to relocate the Project to avoid the Montana Mountains and agreeing to purchase credits under the Nevada Conservation Credit System (CCS) to ensure a net conservation gain to sage-grouse. In addition, LNC argues the Project was not forced to comply with RMP requirements for visual resources because the Project “obviously” cannot be relocated. BLM also retains “a great deal of discretion in deciding how to achieve” compliance with relevant land-use plans. To support this claim, LNC cites a Ninth Circuit Court Case[34] in which the Court denied a preliminary injunction request where plaintiffs alleged BLM violated FLPMA by approving a hardrock mining project that would not likely satisfy visual-impact standards.

Plaintiffs

See Plaintiffs response under section titled “Project approval relied on unsupported assumptions that LNC held ‘valid existing rights’ under the Mining Law of 1872” (Immediately below).

- Project approval relied upon unsupported assumptions that LNC had “valid existing rights” under the Mining Law of 1872

BLM

Plaintiffs argue BLM approved the Project based on the “assumption” that LNC held “valid existing rights” under the Mining Law of 1872. In response, BLM notes it possessed neither a reason nor legal obligation to establish the existence of valid mining claims or sites—including claims on lands to be used for waste dumping—before reaching a decision. The Mining Law states that “all valuable mineral deposits in lands belonging to the United States, both surveyed and unsurveyed, shall be free and open to exploration and purchase…” No law, regulation, or departmental policy requires BLM to determine mining claim validity before approving a plan of operations. By contrast, the Department of the Interior (DOI) may investigate mining claim validity at any time, but this is generally limited to operations involving mineral patents or lands withdrawn from Mining Law protection (e.g., to ensure land/resource preservation). Since the Project is both temporary (no patent required) and comprises entirely of public land, BLM was not obligated to determine mining claim validity.

LNC

While plaintiffs assert BLM must validate all mining claims prior to granting Project approval, LNC, like BLM, argues the Mining Law of 1872 does not require BLM to do so. LNC quotes a related case[35] that confirms this assertion, “…the Mining Law, its implementing regulations, and related case law have never required the DOI or BLM to verify the validity of a claim by independently confirmed discovery”. Mining claims are treated as de facto “valid” until proven otherwise. The Earthworks24 case adds that, formally speaking, a claim is valid against the United States only if the land contains valuable minerals, but in practice, “BLM generally does not determine the validity of the affected mining claims before approving a plan of operations”[36]. LNC believes requiring mining claim validity interferes with the longstanding spirit of free exploration of public lands for mineral discovery and Congress’s repeated efforts to preserve and protect rights under the Mining Law in a way that recognizes the Nation’s need for domestic sources of minerals. One way the FLPMA has amended this Law is through requiring claimants to record each mining claim with BLM and displaying proof of annual assessment work for each claim. However, Congress does not require a validity claim to accept these filings. LNC further cites the Act of July 23, 1955 (Surface Resources Act of 1955)[37] where Congress broadly defines legitimate mining activity to include “prospecting, mining, or processing operations and uses reasonably incident thereto.” This would include the storage of waste rock.

Plaintiffs

Plaintiffs’ main contention with respect to defendants’ FLPMA claims is the fact that defendants misinterpret the statutory rights granted under the Mining Law of 1872. Defendants believe such rights for locatable minerals can be used as a “blanket statement” to avoid compliance with all other land use plans (RMPs), namely ARMPA (sage-grouse) and VRM requirements under Winnemucca, Nevada’s RMP. BLM states, “…such compliance is not required where a planning provision would prohibit exercise of statutory rights under the Mining Law.” However, plaintiffs clarify that the Mining Law only grants the right to occupation and purchase of lands in which valuable mineral deposits are found. The Common Varieties Act of 1955 prohibits the filing of legitimate mining claims that contain only common minerals, i.e., sand, stone, gravel, and has withdrawn such lands from Mining Law protection.

Plaintiffs argue BLM was required to verify that all LNC’s mining claims contained valuable minerals before it could recognize rights under the Mining Law. While LNC intends to designate a portion of the Project area for waste dumping, it has not validated the existence of valuable minerals within these lands. Defendants argue BLM was not required to determine mining claim validity prior to Project approval to guarantee protection under the Mining Law. However, plaintiffs argue BLM was required to perform a common variety determination, independent of a validity claim, to investigate the presence of “common variety” minerals in the designated lands prior to Project approval:

Defendants further cite the Surface Resources Act of 1955[38] to argue BLM can ignore all aspects of the waste dump lands because they are “reasonably incident” to pit mining. Plaintiffs counter by claiming said act was intended to eliminate “abuses under general mining laws by those persons who located mining claims on public lands for purposes other than legitimate mining activity,” and “Congress did not intend to change the basic principles of the mining laws [with that Act].”

According to plaintiffs, LNC neither owns the rights to these lands designated for waste dumping (unless a common varieties determination identifies the presence of valuable minerals), nor is that land protected against other RMP requirements. Indeed, FLPMA requires land use plan (RMP) provisions not to “impair the rights of any locators under that [1872] Act.” Therefore, LNC must obey RMP guidelines for any lands for which it does not own a right to mine, i.e., lands containing common minerals.

Relevant Court Case

An ongoing dispute over an Arizona copper mine sheds some insight into the mining claim dispute. Both sides cite a July 2019 Arizona District Court case[39] in their arguments. The trial addressed the US Forest Service’s failure to conduct a mining claim validity determination on a 2,447-acre “waste dump” located on federal land (Coronado National Forest) prior to approving a large open-pit copper mine’s plan of operations. The Court ruled against the agency’s approval, halting mine construction the day before it was set to begin, declaring, “If there is no valuable mineral deposit beneath the purported unpatented mining claims, the unpatented mining claims are completely invalid under the Mining Law of 1872, and no property rights attach to those invalid unpatented mining claims.” The court deemed this a crucial error that “tainted the Forest Service’s evaluation of the Rosemont Mine from the start.” Hudbay Minerals Inc. and the U.S. Justice Department have since requested further review of the District Court’s decision by a federal three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. In a recent Ninth Circuit Court hearing, neither defendants’ nor plaintiffs’ attorneys could cite an instance in which an individual mine was either required or not required to locate waste on lands with valid mining claims[40]. Hudbay Minerals expects a court ruling by the second half of 2021.

While plaintiffs reference this case to support their claim that the Mining Law does not grant rights for “waste dumping, LNC clarifies that the Earthworks Court found this case to be of “limited relevance” to the issue of whether BLM must determine mining claim validity prior to plan approval. “Although the case examined the Mining Law, it dealt with a site-specific application of Forest Service regulations and a statute unique to the Forest Service.” Nevertheless, the Rosemont litigation is ongoing and offers an interesting comparison to the Thacker Pass case. One key difference between cases, however, is Project location: the Thacker Pass Project will occur solely on public lands, while waste dumping from Rosemont would transpire on federal land.

- Failure to ensure compliance with air and water quality standards and protect public resources

BLM

BLM attests the Project does not violate water-and air-quality standards and prevents “unnecessary or undue degradation (UUD). BLM admits the Project’s mine pit backfill will contain antimony levels that will exceed state regulatory standards for drinking water, but since the groundwater is neither intended for drinking nor will it reach nearby water wells and other sources of potable water, this standard does not apply. Regarding air quality, the agency reaffirms that the FEIS concluded “the estimated maximum ambient concentrations for all pollutants and averaging periods are less than the applicable National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and Nevada Standards.”

LNC

Regarding water quality standards, LNC argues its protocols satisfy NEPA regulations. LNC has developed a groundwater monitoring strategy in accordance with NDEP standards, which includes an “adaptive management approach” to identify and mitigate water quality concerns as they occur over time. While plaintiffs argue the public was not able to comment on BLM’s “late analysis”, LNC affirms this approach is consistent with BLM’s approval of an adaptive management plan. Since LNC predicts impacts to water quality may not occur in the first 10-15 years of operations, this method is appropriate. LNC adds that a technical advisory group comprising of BLM staff and federal, state, and local agency representatives will support monitoring & mitigation efforts.

With respect to air quality standards, LNC argues BLM thoroughly analyzed the Project’s direct and indirect impacts on air quality in accordance with NEPA, FLPMA, and land-use plans. While BLM employed its own methodology to conclude the Project’s air emissions would not exceed both National Ambient Air Quality and Nevada standards, it has deferred to the NDEP—the federally delegated permitting authority under the Clean Air Act— to make a final determination on the Project’s compliance with air quality standards. NDEP is currently reviewing the Project and must issue a permit to LNC before construction can begin. Considering the review, BLM determined “regulatory agencies (NDEP) charged with permit enforcement would ensure compliance with the permit requirements.”

Plaintiffs

Plaintiffs argue BLM’s approval of the Project’s water and air quality standards contain several violations. According to both Nevada groundwater protection laws and findings by the Nevada Department of Environmental Protection (NDEP), the Project’s open pit backfilling of waste rock and gangue material will release pollutants, namely antimony, into groundwater and violate Nevada state drinking water standards for up to 300 years post closure. On May 5, 2021, NDEP informed LNC and BLM that the mine’s excavation below the water table was illegal. It implemented a permit limitation to “restrict mining below the water table (regional aquifer) until additional studies can be completed and a mine plan is proposed which does not result in the degradation of waters of the State.” Nevertheless, BLM approved the entire project, including excavation of the mine pit into the aquifer. While LNC has since developed a comprehensive water quality monitoring plan to monitor these predicted violations, plaintiffs point out that, since BLM already submitted its ROD, this mitigation plan is not subject to public review and violates NEPA’s goal of affording the public a role in land-use decision-making. In any case, defendants claim the contaminated water would not be designated for drinking, nor would it contaminate other sources of potable water. However, plaintiffs urge the groundwater could become a source of drinking water in the future as climate change dries up nearby water supplies.

Regarding air quality, plaintiffs reinforce the necessity for public review in land-use decision-making. BLM cannot rely on NDEP air permits as a substitute for full public review of mining projects under NEPA. “[a] non-NEPA document…cannot satisfy a federal agency’s obligations under NEPA.” Plaintiffs are also unsure of LNC’s “tail gas scrubber” technology LNC claims it will use to meet strict toxic air emission standards, but this is merely a technical issue—BLM was afforded some deference regarding the technology’s approval. Nevertheless, plaintiffs are unaware of how this device works and question why it could not be developed and submitted for public review.

- Failure to adequately analyze the background/baseline conditions[41] of the Project

BLM

BLM declares it took a “hard look” at Project impacts to four priority animals—sage-grouse, pronghorn, three species of amphibians, and two species of springsnails—by conducting robust baseline surveys within the Project area. BLM surveyed 113 transects in 15 sample units across approximately 49,165 acres of land, identifying one active sage grouse lek (breeding ground) in the Project vicinity. BLM mapped pronghorn movement between summer and winter habitats throughout the year and identified 427 acres of summer habitat and 4,960 acres of winter habitat that would be adversely affected by the Project. After conducting baseline surveys for springsnails and amphibians, BLM determined only one of three amphibian species (Pacific tree frog) and no springsnail species would be adversely affected.

LNC

LNC argues BLM performed extensive reviews of baseline conditions for all priority species. Notably, the FEIS did describe the Project’s impacts on pronghorn populations due to clearing of nearly 5,000 acres of its habitat, including how habitat fragmentation from construction would likely prohibit or impede pronghorn movement between seasonal habitats and increase the difficulty of finding food. While plaintiffs have urged BLM to develop mitigation measures for both amphibians and springsnails, LNC clarifies that NEPA does not require adoption of mitigation measures, nor would either species likely occur in the Project area. The agency conducted a multitude of surveys to ensure neither species would be present in the Project area.

Plaintiffs

Plaintiffs argue BLM did not thoroughly review baseline conditions for priority animals. They allege defendants offered vague statements that lack thorough analysis of sage-grouse habitat use and how noise disturbance to two nearby leks, Montana-10 and Pole Creek, would impact populations. BLM’s analysis of Pronghorn does not address the species’ declining numbers statewide, referring to populations as stable, nor does it reveal the harm pronghorn would face given the destruction of 5,000+ acres of habitat. Defendants dismiss impacts to springsnails altogether, which would lead to groundwater drawdowns that would affect 5 of 13 total springs known to support Kings River pyrg.

- Failure to adequately analyze direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts of the Project

BLM

BLM asserts its cumulative-impacts analysis complied with NEPA, which is included in chapter 5 of the FEIS. BLM identified, described, and mapped cumulative effects to study areas, identified relevant past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions, and described and quantified (where possible) impacts of various projects on wildlife, air quality, and other vulnerable resources. Plaintiffs argue BLM did not address potential impacts from a nearby McDermitt lithium mine (Figure 4), nor were its cumulative effects study areas for sage-grouse and other wildlife sufficient to include all potentially affected populations (Figure 6). However, because these objections were not raised during the appropriate public scoping/commentary period prior to Project approval, these objections are “forfeited” upon judicial review.

LNC

According to LNC, while plaintiffs claim the FEIS’s cumulative impacts analyses merely listed acreages of various other projects in the area without providing “some quantified or detailed information”, LNC argues the contrary. LNC highlights chapter 5 of the FEIS to reveal thorough examinations of potential effects on geology and minerals, air quality and greenhouse gas emissions, and wildlife and special status species. LNC points to a Ninth Circuit Court case[42], which ruled an agency “is free to consider cumulative effects in the aggregate or to use any other procedure it deems appropriate. It is not for this court to tell the [agency] what specific evidence to include, or how specifically to present it.” Regarding plaintiffs’ argument that the geographic scope of BLM’s sage-grouse analysis is too narrow and should have extended beyond the Lone Willow PMU into Oregon, LNC argues BLM’s selection was based on the appropriate factors, e.g., type of species potentially harmed, biological use of the area, and prior management of the target species. In any case, LNC reminds plaintiffs that Courts must afford BLM considerable deference when selecting the geographic scope of a cumulative effect analysis[43].

Plaintiffs

According to plaintiffs, BLM’s FEIS provided an insufficient assessment of the cumulative impacts from related activities in the Project Area. Their main contention is BLM’s omittance of an effects analysis on the nearby McDermitt Lithium Project and a failure to perform a larger-scope analysis on sage-grouse populations. While defendants believe plaintiffs “waived” these issues by failing to specify them during the public scoping period, plaintiffs believe they were not required to clarify every single concern for BLM to include them in their cumulative impacts analysis. They cite a Ninth Circuit Court case[44] involving BLM’s faulty approval of a gold mining exploration plan for northeastern Nevada, which concluded, “Plaintiffs met their burden in raising a cumulative impacts claim under NEPA, despite failing to specify a particular project that would cumulatively impact the environment along with the proposed project…We conclude that Plaintiffs must show only the potential for cumulative impacts.” Plaintiffs believe the concerns they raised in the public scoping period, while vague, were enough to persuade BLM to include such issues in their analysis. And while BLM addressed cumulative effects on sage-grouse populations, plaintiffs believe this information was inadequate and did not quantify the entire destruction the Project would inflict on both the Pole Creek lek and Montana-10 lek, the latter being one of the three largest sage-grouse leks in the 480,000-acre Lone Willow Population Management Unit (PMU)[45].

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Figure 4. Location of Thacker Pass in relation to McDermitt Project. Source | Figure 5. Location of Thacker Pass Project relative to Nevada and nearby states. Source | Figure 6. Nevada Sage-Grouse Population Management Units (PMUs). The Lone Willow PMU (black circle) surrounds the Project area Source |

- Failure to adequately analyze potential mitigation measures and their effectiveness

BLM

BLM claims its consideration of mitigation measures for the Project satisfies NEPA’s requirement that an EIS contain “a reasonably complete discussion of possible mitigation measures.” NEPA does not require an agency to formulate and adopt a complete mitigation plan. Nevertheless, BLM immediately analyzed groundwater mitigation protocols regarding the presence of a mine backfill and selected Alternative A in its ROD. The FEIS contains an additional “comprehensive groundwater quality monitoring plan” that is subject to BLM and NDEP review/approval prior to major construction. Finally, LNC adopted a “wait and see” mitigation approach to address specific water quality concerns on a case-by-case basis “given the relatively low probability and temporal remoteness of adverse impacts to ground water.” As previously noted, BLM determined the Project will meet state air quality standards and was not required to adopt a related mitigation strategy.

Regarding public mitigation proposals presented during scoping intervals, the agency insists it considered all public comments on the FEIS, including suggestions from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW), but it was not obligated to implement their recommendations. BLM deemed the suggestions unnecessary and stressed that the FEIS analysis utilized standard protocols and “applied all reasonable and feasible mitigation within its regulatory authority regarding water resources…and other resource topics.”

LNC

According to LNC, plaintiffs object to LNC’s adaptive management approach, arguing LNC did not fully develop a mitigation and monitoring plan. LNC reiterates how its flexible, “conceptual” framework is advantageous for a project whose potential impacts are uncertain and may occur years (or decades) in the future. LNC notes multiple examples where courts have approved such plans, including a case[46] in favor of an open-pit molybdenum mine in Nevada that adopted a “wait and see” monitoring and mitigation approach. Early hydrological and geochemical modeling regarding the Project predict groundwater seepage into the mine pit, i.e., drawdown of the local water table, would not begin until 2035. After the pit is backfilled at the end of the mine life, the antimony-rich water would migrate no farther than one mile over the simulated 300-year post closure period. These (and other) examples support LNC’s decision to adopt a proper management strategy. As an additional measure, LNC’s water and wildlife technical advisory groups will actively participate in the ongoing monitoring and mitigation process. With respect to the public scoping periods, LNC supports BLM’s decision to decline comments/suggestions from EPA and NDOW regarding the FEIS during the scoping process as it, too, believes the FEIS employed sufficient science, data, and methodologies to develop suitable protocols.

Plaintiffs

Plaintiffs focus primarily on sage-grouse protections when discussing BLM’s inadequate mitigation strategy. Volume 65 of BLM’s Federal Register reads, “An impact that can be mitigated, but is not, is clearly unnecessary.”[47] Plaintiffs argue defendants failed to implement a sage-grouse mitigation plan consistent with ARMPA, which they believe could have been developed in a manner that preserves LNC’s alleged “mining rights.” They cite a Nevada District Court case[48] that concluded, “…if actions by third parties result in habitat loss and degradation, even after applying avoidance and minimization measures, then compensatory mitigation projects will be used to provide a net conservation gain to the sage-grouse.” Despite this, BLM approved the ROD with no sage-grouse mitigation plan in place and none provided for public review.

- Authorization of unnecessary or undue degradation (UUD) of the land within the Project area

The FLPMA requires the Secretary of the Interior, in managing public lands, to “take any action necessary to prevent unnecessary or undue degradation of the lands,” which is defined as “surface disturbance greater than what would normally result when an activity is being accomplished by a prudent operator in usual, customary, and proficient operations of similar character…”[49]

Plaintiffs declare all preceding allegations to be violations of FLPMA’s UUD standard, which include alleged damage to water and air quality, wildlife, and individuals within or near the Project area. In response, BLM argues it correctly determined the Project would not violate FLPMA’s UUD criteria. LNC adds the following in support of BLM’s decision:

LNC

Plaintiffs believe BLM did not implement the necessary mitigation measures to satisfy ARMPA (sage-grouse) requirements. As previously noted, however, BLM must only comply with land use plans to the degree that they are consistent with the Mining Law, i.e., they cannot infringe on mining rights. LNC also argues plaintiffs are equating ARMPA’s provisions to a “federal law”, though these requirements are more stringent than what is required under the UUD minimum standard for BLM’s land management policy. For those reasons, BLM’s current UUD mitigation procedures with respect to sage-grouse are sufficient.

- Failure to determine reclamation costs and obtain related financial assurances

Plaintiffs

Plaintiffs argue BLM’s failure to report the Project’s full reclamation and related costs as well as a Long-Term Funding Mechanism (LTFM) as part of its ROD approval violates FLPMA implementing regulations. LNC must generate an LTFM to finance its long-term management and containment of water utilized and/or contaminated by the Project. Plaintiffs cite, “You must establish a trust fund or other funding mechanism available to BLM to ensure the continuation of long-term treatment to achieve water quality standards and for other long-term, post-mining maintenance requirements.” While BLM’s FEIS contains a Reclamation Cost Estimate (RCE) for the Project’s north/south exploration plans, neither the ROD nor FEIS mention an official RCE for all Project operations (mining + exploration). Plaintiffs note that the BLM addressed the need for an RCE but has yet to submit one:

BLM

BLM cites a declaration provided by Kathleen L. Rehberg, who has served as Field Manager at BLM’s Humboldt River Field Office since January 19, 2021 (after the ROD was signed) and worked for the agency for 13 years, to show BLM is, in fact, engaged with BLM and NDEP in financing discussions. Rehberg’s declaration reads:

LNC

LNC does not present any support evidence on the matter.

III. The public interest and balance of equities favor an injunction.

BLM

BLM believes both public interest and a balance of equities outweigh the merits of injunctive relief for two reasons. First, relief will interfere with data & sample collection under the HPTP, thus inhibiting goals of the NHPA to establish a meaningful coexistence between modern society and the nation’s historic lands. Second, injunctive relief will delay the overall timeliness of the Project itself, which goes against Congress’s statutory objectives outlined in the FLPMA to manage public lands “in a manner which recognizes the Nation’s need for domestic sources of minerals, food, timber, and fiber from the public lands including implementation of the Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970[50] as it pertains to the public lands…”

LNC

LNC states the merits of the Project are clear: the Project’s projected capacity of 66,000 tons per annum will play an essential role in supporting the U.S.’s efforts to regulate the global climate and fortify the Nation’s security. President Biden’s Executive Order 14017 highlights the need for the U.S. to leverage domestic lithium reserves to bolster electric vehicle battery production to help “tackle the climate crisis.” Reducing the Nation’s dependency on foreign entities for lithium and other critical minerals will also bolster national security. The Project’s economic benefits to Humboldt County, including employment and tax revenue, are apparent as well; LNC has engaged with local tribes to develop a skilled workforce and believes tribal members support the Project.

Plaintiffs

Plaintiffs believe their interests face permanent, irreparable harm from the Project, while a ruling for injunctive relief will only delay the Project temporarily. The sole fact that permanent damage to wildlife, individuals, and the environment is at stake as opposed to, at most, a temporary impediment to a mining schedule, validates the need for injunctive relief.

Appendix A – Acronyms

APA – Administrative Procedure Act

ARMPA – (Greater Sage Grouse) Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment

BLM – Bureau of Land Management

CCS – Conservation Credit System

DOI – Department of the Interior

EA – Environmental Assessment

EIS – Environmental Impact Statement

- DEIF – Draft EIS

- FEIS – Final EIS

EPA – Environmental Protection Agency

ESA – Endangered Species Act

FLPMA – Federal Land Policy and Management Act

HPTP – Historical Properties Treatment Plan

LAC – Lithium Americas Corporation

LNC – Lithium Nevada Corporation

LTFM – Long Term Funding Mechanism

MFP – Management Framework Plan

NDEP – Nevada Department of Environmental Protection

NDOW – Nevada Department of Wildlife

NEPA – National Environmental Policy Act

NHPA – National Historical Preservation Act

NOA – Notice of Availability

NOI – Notice of Intent

PFS – Pre-Feasibility Study

RCE – Reclamation Cost Estimate

RMP – Resource Management Plan

ROD – Record of Decision

UUD – Unnecessary or Undue Degradation

VRM – Visual Resource Management

Appendix B – BLM Staff Bios

- BLM Staff Responsible for Project Approval

Winnemucca District Office

https://www.blm.gov/office/winnemucca-district-office

Ester McCullough – District Manager

- Authorized EIS and ROD

Office Field Managers

Kathleen Rehberg – Humboldt River Field Office

Mark Hall, PhD – Black Rock Field Office & Station

BLM Nevada State Director

Jon Raby

A. Ester McCullough

Began as District Manager on April 16, 2018

1994 – 2001: Acting Natural Resources Officer (Environmental Protection Specialist) for Naval Air Station Fallon

2001- 2003: Planning and Environmental Coordinator in BLM Nevada’s Winnemucca District

- Led Black Rock National Conservation Area Resource Management Plan planning effort

- Received Outstanding Federal Project Planning Award from American Planners Association

2003 – 2008: Natural Resource Planner on the Nez Perce National Forest for the US Forest Service

2008 – 2011:

(1) Project manager in BLM Idaho’s Jarbidge Field Office, Twin Falls District

- Managed major Rights of Ways for wind energy and pipeline projects

(2) Assistant Field Manager for Minerals and Lands in BLM Wyoming Rawlins Field Office

2011-2015: Associate Field Manager for BLM Colorado White River Field Office

2018 – Present: District Manager for BLM Nevada, Winnemucca District

B. Kathleen Rehberg (geologist)

(Writes a Declaration on pg. 220 of BLM response)

- Field Manager at Humboldt River Field Office, BLM since January 19, 2021 (after the ROD was signed)

- Served as Assistant Field Manager for Minerals at the Humboldt River Field Office during the time the EIS was being prepared and the ROD was signed

- Employed by BLM for 13 years

- Prior to current role, she served as Assistant Field Manager for Minerals and a Geologist for the Winnemucca District

Key Roles

- Project Lead on three Environmental Impact Statements (EISs), five Environmental Assessments (Eas), and other minerals projects

- Project Lead and Geologist for previous mining and exploration activities in the Thacker Pass Mining Project, which were conducted by Lithium Nevada Corp. and its predecessors and approved by BLM

- As Field Manager, she oversees authorized & proposed activities on public lands that occur within her office area and supervises staff in Minerals, Range, Recreation, Cultural, Natural Resources, and Lands, Divisions within the Field Office

- Resource staff from these divisions worked on the EIS for the Thacker Pass Project, which resulted in the eventual ROD signed January 15, 2021 (by Ester McCullough)

Kathleen Rehberg did not oversee the staff that worked on the EIS for Thacker Pass. She was a part of the Minerals staff that worked directly on the EIS

C. Mark Hall, PhD (archaeologist)

(Declaration located on pg. 47 of BLM response)

- Field Manager at Black Rock Field Office & Station, BLM since November 2017

- Employed by BLM for 11.5 years (since January 2010)

- Prior to current role, he served as Assistant Field manager for BLM Winnemucca District Office, a planning and environmental coordinator, a project manager, and an archaeologist.

- Was also a consultant performing archaeological and ethnographic studies for Cultural Resource Management contractors and with tribes in California and Nevada

- Over the past two years, Hall has presented papers and posters on the archaeology of the Winnemucca District at the American Geophysical Union conference, European Geophysical Union conference, Society for California Archaeology conference, and the 2021 Society for American Archaeology conference.

- Hall possesses the authority to sign decision documents for projects on public lands in the jurisdiction of the Black Rock Field Office

- The Winnemucca District Office (WDO) senior archaeologist (who was assigned to the Thacker Pass Project) took a new position in Arizona. WDO’s two other archaeologists are new recruits, whom Hall is currently mentoring and training. Due to this situation, Hall is familiar with the Thacker Pass Project and specifically the Historic Properties Treatment Plan (HPTP) and the Project’s compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). Hall provides a declaration on behalf of BLM due to his experience & knowledge of the Project. His points include: (See declaration on pg. 47 for all points).

D. Jon Raby

BLM Nevada State Director

BLM Tenure – 20 years

Raby does not appear to be directly involved in the Thacker Pass Case, but he is the BLM state director of Nevada, i.e., highest authority.

State-Director’s-Priorities-2021.pdf (blm.gov)

Appendix C: Lone-Willow Population Management Unit

DISCLOSURES

General Firm

Formidable Asset Management, LLC (Formidable) is an investment adviser registered under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Registration as an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training. The information presented in the material is general in nature and is not designed to address your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. Prior to making any investment decision, you should assess, or seek advice from a professional regarding whether any particular transaction is relevant or appropriate to your individual circumstances. Although taken from reliable sources, Formidable cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information received from third parties.

The opinions expressed herein are those of Formidable and may not actually come to pass. This information is current as of the date of this material and is subject to change at any time, based on market and other conditions. Any index performance cited or used throughout is intended to illustrate historical market trends and performance. Indexes are managed and do not incur investment management fees. An investor is unable to invest in an index. The performance shown may not reflect a Formidable portfolio.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Reader should assume that future performance of any specific investment or investment strategy (including the investments and/or investment strategies discussed in these materials) referred to directly or indirectly in these materials will be profitable or equal the corresponding indicated performance level(s). Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment will either be suitable or profitable. Historical performance results for investment indices and/or categories generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges, the deduction of an investment management fee, nor the impact of taxes, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results.

Specific Securities

The mention of specific securities and sectors illustrates the application of our investment approach only and is not to be considered a recommendation by Formidable. The specific securities identified and described above do not represent all the securities purchased and sold for the portfolio, and it should not be assumed that investment in these securities were or will be profitable. There is no assurance that the securities purchased remain in the portfolio or that securities sold have not been repurchased. Charts, diagrams, and graphs, by themselves, cannot be used to make investment decisions. You may contact Formidable Asset Management, LLC for a full list of recommendations made during the preceding period one year

Not an Offer

These materials do not constitute an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security or any other product or service by Formidable or any other third party regardless of whether such security, product or service is referenced here. Furthermore, nothing in these materials is intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice and nothing in these materials should be construed as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any investment or security or to engage in any investment strategy or transaction. Formidable does not represent that the securities, products, or services discussed here are suitable for any particular investor. You are solely responsible for determining whether any investment, investment strategy, security or related transaction is appropriate for you based on your personal investment objectives, financial circumstances and risk tolerance. You should consult your business advisor, attorney, or tax and accounting advisor regarding your specific business, legal or tax situation.

The opinions expressed here are those of Will Brown and Adam Eagleston are not intended as investment advice. They are also subject to change with changing market conditions. Clients of Formidable may have positions in securities discussed in this article. This writing is for informational purposes only—Formidable and the authors expressly disclaim all liability in respect to actions taken based on any or all of the information from this writing.

[1] The Project is generally projected to begin major construction in 2022. It is estimated to house approximately 33ktpa (phase I) and 66ktpa (phase II) of LiCO3 per annum of total capacity by year three (2024) and year seven (2028) of operations, respectively, over the estimated 41-year mine life (“Thacker Pass Lithium Mine Project: Final Environmental Impact Statement” (U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Dec. 4, 2020), chapter 1:2; chapter 4:86).

[2] Bartell Ranch, LLC v. Ester M. McCullough, United States District Court District of Nevada, Case No. 3:21-cv-00080, “Complaint”, filed 02/11/21.

[3] Western Watersheds Project v. United States Dep’t of the Interior, United States District Court District of Nevada, “Complaint for vacatur, equitable, declaratory, and injunctive relief, filed 02/26/21.